The Dakota 38

The Dakota 38

On December 26, 1862 – the day after Christians celebrated Christmas, billed as a season of “goodwill towards men” – the largest mass execution in United States history was carried out in Mankato, Minnesota. A special gallows had to be created in order to accommodate the large number of condemned.

Due to almost the entire tribe being incarcerated en masse on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, it is speculated that very few, if any, friends or family of the condemned were available to comfort the prisoners in their last hours or to attend the execution of their loved ones. There probably weren’t any friendly faces to see in the crowd before their death at the hands of the United States government.

Background

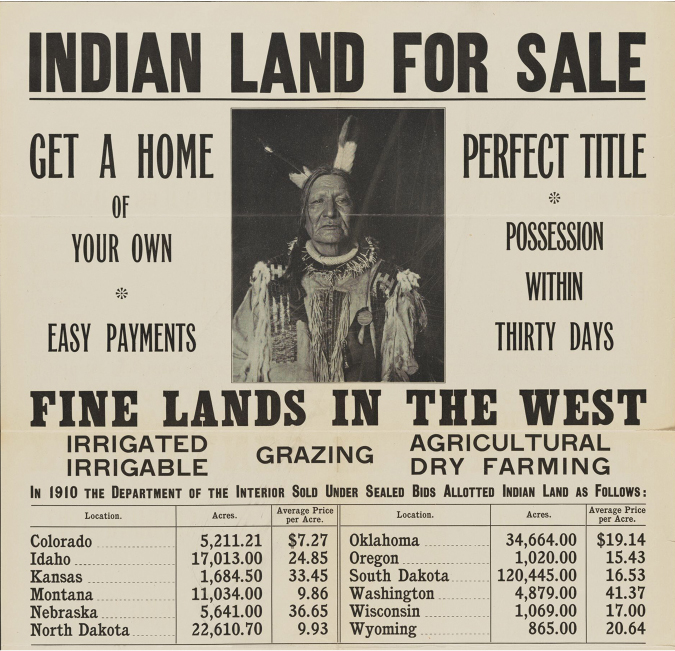

It all started with the treaties, as it so often does. Specifically, the US not honoring their commitment set out in the treaties with the Dakota tribes in the area that is now Minnesota. In a series of treaties between 1837 and 1858, the Dakota had exchanged land for money and food. The US at the same time encouraged settlers to homestead in the newly acquired Dakota lands. The US honored the treaties for a few years, and even though there was tension between the settlers and the tribes, there were no recorded outright hostilities between them.

Then came the civil war. Historians tentatively agree that the war between the states distracted the US government from honoring its commitments to the tribes, or perhaps Congress felt that resources should be allocated elsewhere. Whatever the reason, food and money stopped arriving. Game was scarce due to settlement activity, so the Dakota people were soon on the verge of starvation. Something had to give.

On August 17, 1862, a chief of the Mdewakanton Dakota named Little Crow was leading a hunting party when they came across the settlement of Acton Township. The Dakotas grabbed some eggs, which led to an armed altercation in which five settlers died.

Little Crow decided on August 18 to start leading raids against the settlers. They attacked the Lower Sioux Agency near Morton, MN, then went on to raid New Ulm and Fort Ridgley. As there were very few soldiers available to lead counter attacks against the Dakota, a volunteer militia formed up. It was led by former governor Henry Sibley. At first the militia were routed by the Dakota, but on September 23, the militia defeated the Dakota at the Battle of Wood Lake in Yellow Medicine County. On September 26, the Dakota formally surrendered. They released the nearly 300 captives they had collected in the six weeks they had been raiding. In return, the militia forcefully rounded up every Dakota they could find and removed them all to Pike Island.

The starvation of the people continued but now they had to contend with disease as well. Hundreds of women, children, and the elderly died. The men were held separately from their families at Camp Release until November, when the so-called trials started.

Lincoln's Legacy

There were 498 trials, conducted exclusively in English, in which the men were denied legal representation. They were charged with crimes from rape to murder in trials that were insanely quick – some lasted less than five minutes. Of these 498 trials, 300 men were found guilty and sentenced to death.

Then president Abraham Lincoln personally read through the trial transcripts. He determined that of the 300, all but 38 would have their sentences commuted to four years imprisonment at Camp McClellan. The 38 who were to be executed were those deemed to have committed offenses against civilians.

The executions were carried out on December 26 of that year.

A mere 5 days later, on January 1, 1863, former President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. His face is now immortalized on Mount Rushmore, a granite escarpment which was formerly known as the Tunkasila Sakpe Paha, or Six Grandfathers Mountain. This usurping of the Tunkasila Sakpe Paha is an enormous insult to all Indigenous peoples, and the struggle surrounding the Black Hills is a story in its own right.

In April 1863, Minnesota voided all treaties with the Dakota and sent all of the survivors to Nebraska. Then, the state congress enacted legislation making it illegal for any Dakota to live in Minnesota.

“The state reward for dead Indians has been increased to $200 for every red-skin sent to Purgatory. The sum is more than all the dead bodies of all the Indians east of the Red River are worth.” – The Daily Republican, Winona, MN, 1863

The bounty on scalps was successful. Among others, Little Crow was killed and his scalp was collected for the bounty. Furthermore, his skull was kept by the family as a memento until 1971. The last formal execution of a Dakota was in 1865

Present Day

A memorial honors the 38 in Mankato. A “Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation” was signed on August 17, 2012 by Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton, and the Minneapolis and St. Paul city councils declared 2013 “The Year of the Dakota.” The word “genocide” was used in their formal resolutions.

As of this writing, negotiations are underway to transfer Upper Sioux Agency State Park to the local Dakota tribe, according to a report by The Guardian. The Dakota 38 are buried somewhere on this land, and proponents say it is right and correct that their descendants be able to visit the graves without paying a fee.

Granite Falls is a nearby town that is opposing the transfer due to projected loss of recreation fees from those who wish to utilize the trails. Since the exact location of the burials is unknown, the potential for people to be mountain biking over a grave is high.

Meanwhile, the law enacted by the state making it illegal for any Dakota to be in Minnesota has never been repealed.

The 38 Condemned

- Tipi-hdo-niche (Forbids His Dwelling)

- Wyata-tonwan (His People)

- Taju Xa (Red Otter)

- Hinhan shoon koyag mani (Walks Clothed In An Owl’s Tail)

- Maza bomidu (Iron Blower)

- Wapa duta (Scarlet Leaf)

- Wahena

- Sna mani (Tinkling Walker)

- Rda inuanke (Rattling Runner)

- Dowan niye (The Singer)

- Xunka ska (White Dog)

- Hepan (family name for Second Son)

- Tunkan icha ta mani (Walks With His Grandfather)

- Ite duta (Scarlet Face)

- Amdacha (Broken To Pieces)

- Hepidan (family name for Third Son)

- Marpiya te najin (Stands On A Cloud or Cut Nose)

- Henry Milord (French mixed blood)

- Chaska dan (family name for First Son), aka Dan Little

- Baptiste Campbell (French mixed blood)

- Tate kage (Wind Maker)

- Hapinkpa (Tip Of The Horn)

- Hypolite Auge (French mixed blood)

- Nape shuha (Does Not Flee)

- Wakan tanka (Great Spirit)

- Tunkan koyag i najin (Stands Clothed With His Grandfather)

- Maka te najin (Stands Upon Earth)

- Pazi kuta mani (Walks Prepared To Shoot)

- Tate hdo dan (Wind Comes Back)

- Waxicun na (Little Whiteman)

- Aichaga (To Grow Upon)

- Ho tan inku (Voice Heard In Returning)

- Cetan hunka (The Parent Hawk)

- Hda hin hda (To Make A Rattling Noise)

- Chanka hdo (Near The Woods)

- Oyate tonwan (The Coming People)

- Mehu we mea (He Comes For Me)

- Wakinhyan na (Little Thunder)

Notes

The More You Know series serves as an introduction and starting point in your journey of knowledge on any of the subjects it covers. The articles aim to give a basic overview of the subject and are intended to start conversations and inspire further research.

Suggested Reading

Learn more about the Dakota 38

Further Reading:

“38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End” by Scott W. Berg

- ISBN-13: 978-0307377241

- Relevant Chapters: 6-10 discuss the events of 1862 and the trials that followed.

- Available on Amazon

“Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota” by Gwen Westerman and Bruce White

- ISBN-13: 978-0873518695

- Relevant Sections: Pages 180-200 focus on the Dakota War and its aftermath.

- Available on Amazon

“Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862” edited by Gary Clayton Anderson and Alan R. Woolworth

- ISBN-13: 978-0873511627

- Relevant Sections: The narratives in the second part provide first-hand accounts from Dakota individuals.

- Available on Amazon

U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 – Minnesota Historical Society

- An online resource with articles, photographs, and primary source documents.

Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice

- An exploration into the legal aspects surrounding the trials and subsequent execution of the Dakota 38.